Concept: Sandra Teitge

To celebrate 30 years of ifa Gallery Berlin, this podcast brings together artistic and curatorial positions associated with the gallery since its founding in 1991. Using the gallery’s program as a reference point, selected guests converse with Sandra Teitge about its thematic focal points over the last 30 years. In contrast to many West German cultural institutions of the time, ifa Gallery Berlin concentrated early, throughout the 1990s, on collaborations with artists and curators from Eastern and Southern Europe. How have artistic approaches, curatorial practices and working methods changed over the years? And what is the situation regarding public space, which historically has been more actively incorporated into artistic practices in Eastern and Southern Europe? Does it still provide scope for action in the region? The podcast links these and similar questions to wider contemporary issues and gives a voice to local artists and cultural practitioners.

For the first episode of Past –> Present, Sandra Teitge talks to Berlin-based curator and artistic director of the KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art Kathrin Becker and to the St. Petersburg-based artist Dmitry Vilensky from the collective Chto Delat (What is to be done?). The two of them converse about their respective work with and beyond ifa; their exchange is accompanied by an audio contribution by the Berlin-based music & performance duo R&D who also produced a bonus track that add to this conversation.

Additional Music: Kolbeinn Hugi

Sound editing: Kolbeinn Hugi

Thanks: Ev Fischer, Inka Gressel, Wiley Hoard

Welcome to Past –> Present. Celebrating 30 years of ifa-Galerie Berlin

I’m Sandra Teitge, Berlin-born and based curator and researcher, and the moderator of this podcast.

Past –> Present brings together artistic and curatorial positions associated with the ifa-gallery since its founding in 1991. Using the gallery’s program as a reference point, I will converse with a group of guests about ifa’s general ethos and research interests in the early 90s and today.

What’s the relevance of cultural institutions that foster artistic & cultural exchange, such as ifa, back then and now (especially in times of rising nationalism and cultural isolation)?

In contrast to many West German cultural institutions of the time, the ifa Gallery Berlin concentrated early, throughout the 1990s, on collaborations with artists and curators from Eastern and Southern Europe. How have artistic approaches, curatorial practices and working methods changed over the years? And what is the situation regarding public space, which historically has been more actively incorporated into artistic practices in Eastern and Southern Europe?

This podcast links these and similar questions to wider contemporary issues and offers a podium to artists and cultural practitioners affiliated with ifa at some point in their career.

Today, for this first episode of Past –> Present, I’m very happy to welcome / give the floor to Berlin-based curator and artistic director of the KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art Kathrin Becker and to the St. Petersburg-based artist Dmitry Vilensky from the collective Chto Delat (What is to be done?). The two of them will converse about their respective work with and beyond ifa; their exchange is accompanied by an audio contribution by the Berlin-based music & performance duo R&D who also produced a bonus track that add to this conversation.

Before joining the KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art in early 2020, Kathrin Becker was managing director of the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (n.b.k.) and director of the Video-Forum there since 2003/2001. She has organized and curated manifold exhibitions since the early 1990s, quite a few of them either in Russia or presenting Russian artists in Germany and elsewhere. For ifa, Kathrin curated two exhibitions in the 1990s, which focused on art from Russia: one in ’95 called “Contemporary Photography from Moscow” and another one in ’99 entitled “Neues Moskau. Art from Moscow and St. Petersburg.”

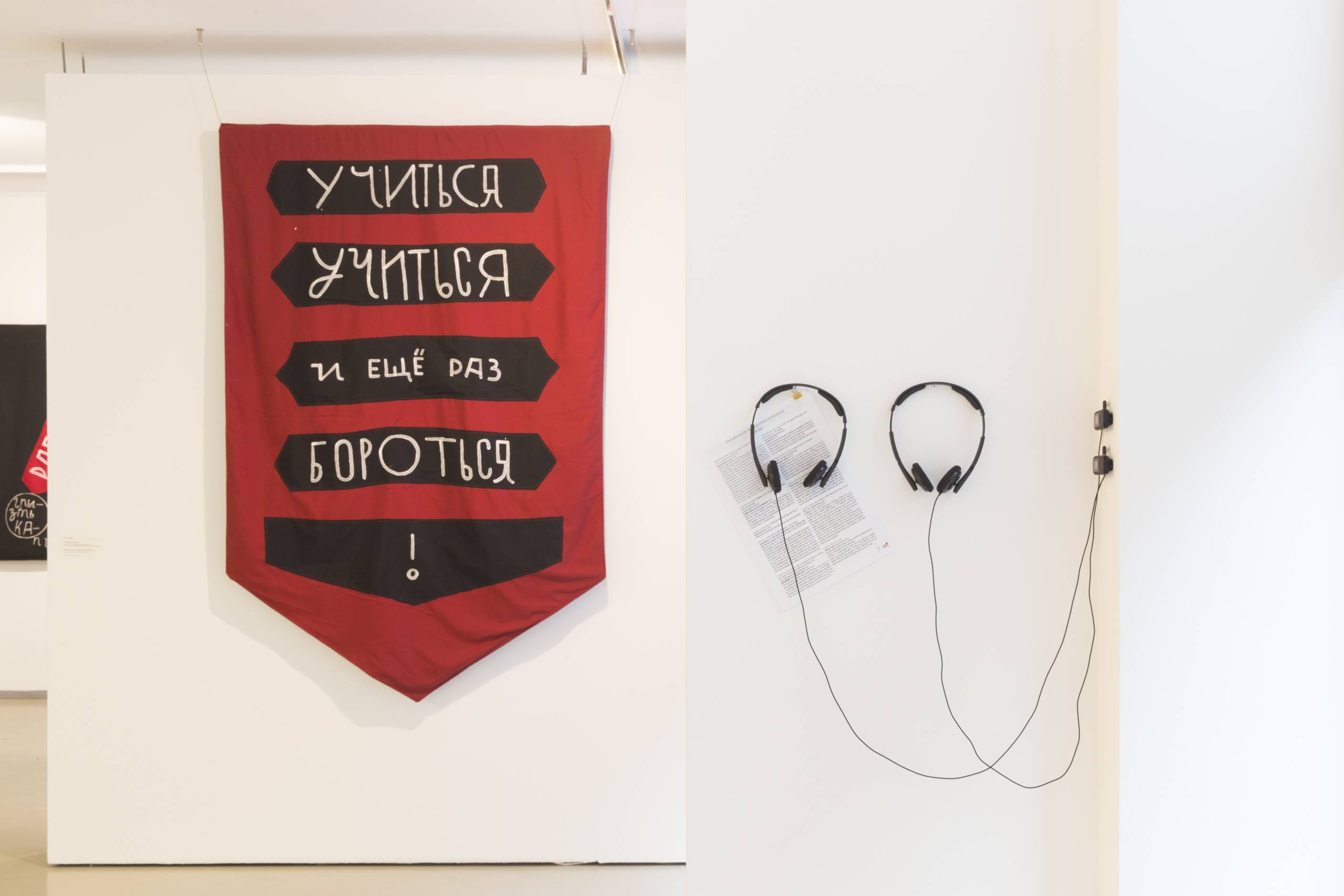

Kathrin will be conversing with D. Vilensky from the collective Chto Delat. Chto Delat (What is to be done?) was founded in 2003 in St. Petersburg by a group of artists, critics, philosophers, and writers with the goal of merging political theory, art, and activism. The group’s ideas are rooted in its members’ active participation in, and research into, current social and political situations in Russia, as well as in principles of self-organization and collective action. In 2015, Chto Delat founded Rosa’s House of Culture, an initiative based on notions of commoning and solidarity economy, that includes the School of Engaged Art, a radical art education initiative, as well as a publicly accessible library dedicated to contemporary art and activist literature. In the context of ifa, Chto Delat participated in the group exhibition “Riots. Slow Cancellation of the Future” in 2018 that was curated by Natasha Ginwala, and is part of the larger project and exhibition series Untie to Tie.

R & D was formed in 2018 by Emilia Kurylowicz, an artist and a filmmaker from Poland, and Maru Mushtrieva, a writer from Russia. Together, they research stereotypes and patterns that are found in their immediate environment, both real and virtual, and use them as a point of departure for their music and performances.

***

ST: Welcome everyone!

Thank you for joining ifa and me today for this podcast.

To start us off, let’s talk about your respective experience of working with and in the ifa-Galerie Berlin.

Kathrin, do you want to start? How did the collaboration come about? What is your connection to Russia? Who did you work with, at ifa?

KB: I did two exhibitions with ifa, one in 1995 and the other one in 1999/2000 at the time when I was a freelance curator in Berlin. The first exhibition was called “Contemporary Photographic Art from Moscow” and it involved a number of artists, like Yuri Babich, Gor Chahal, Fenso-Group, Ilya Piganov, Alexei Shulgin, Anatoli Shuravlev, IV. Vysota – two collectives curiously.

[R & D]

KB: And how did this come along? The former director of the n.b.k., Alexander Tolnay, initiated this series, “Contemporary Photographic Art from” … and Moscow was the first exhibition within this series of exhibitions all dealing with photographic art scene of different countries. This was a collaboration between neuer berliner kunstverein, Academy of Arts, and ifa, actually.

[R & D]

KB: I collaborated with Barbara Barsch, the former director if the ifa-galerie Berlin, and Ev Fischer. The idea behind this project was that photography or photographic art, photo-based art only in the late 1980s, early 1990s became a real subject of public collecting in Russian museums. So the motor of this exhibition was to deal with an aspect of Russian artistic production that in some sense is probably overlooked, even in the country.

[R & D]

KB: The other project was called “New Moscow.” This was the second exhibition I curated for ifa. The subtitle was “Art from Moscow and St. Petersburg” and the participants were Andrei Chlobystin, Vladislav Mamyshev, Timur Novikov, Inspection Medical Hermeneutics…. actually, it was Pavel Pepperstein who participated, and Yevgeniy Yufit. For this project Barbara Barsch and me and the artists Rémy Markowitsch went on a research trip to Moscow. The inspiration for this project was the fact that a new spirit came up in terms of public art in the capital.

[R & D]

KB: Georgian sculptor Zurab Tsereteli in close connection with Moscow’s mayor of that time, Yury Luzhkov a.k.a. The King of Moscow, erected a huge number of super monuments in Moscow that inaugurated a new understanding of culture replacing the former Soviet content through nationalistic and religious tendencies but using the same 19th century monumental language…

There are a few famous ones by Zurab Tsereteli in Moscow, like the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, the Manege Square Ensemble, the War Memorial Complex on Poklonnaya Gora and last but not least the Monument for Peter the Great from 1997. That Tsereteli originally designed to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the first trip of Christopher Columbus in 1992. But no American customer was found for the monument so then the head was replaced by the head by Peter the Great.

[R & D]

KB: It was gigantic. 1000 tons of weight; 600 tons of stainless steel and bronze and copper. This was very curious to me, to see this tendency. Barbara Barsch and me went to, first of all, to interview the artist, Zurab Tsereteli. We had a document of Tsereteli’s monuments in the catalogue. But then, of course, we exhibited works by artists that ironically dealt with new tendencies in the Russian scene or culture. Just to give you an example a drawing by Pavel Pepperstein, for instances, was called “Monument to Someone with too long Hair” – quite a direct commentary on what was then coming up in Moscow. And also the title, “New Moscow,” referred to a famous Socialist painting of Yuri Pimenov of 1937, which commented on the fact that new monuments in Moscow were not so new at all, aesthetically, and also in their imperial attitude.

[R & D]

KB: These were the two projects I did for ifa. Maybe this shows already that I’m talking about a time that is 20-25 years ago.

ST: When one looks back at the exhibitions of ifa, the approach in the early 90s or 90s was very different to what it is now. The group show that Chto Delat participated in reflects this newer approach, I would say, where there is more of a thematic approach rather than a national approach what you described Kathrin, where it was focused on one country.

KB: Well, yes. But you also have to see that it was a totally different time. In the 1990s the world was much smaller than it is now. Imagine that in Europe, even the Internet was not available in a broad sense to a lot of people. To find an artist, for example in St. Petersburg or in West Africa or in Australia, you needed to travel there; you needed to have local connections. There was no checking out artist portfolios on the website. And also not so many people, for example, Russian artists, spoke English at the time. So there were a lot of different questions. Imagine, the first exhibition that exhibited 50% of Western artists and 50% of non-Western artists shoulder to shoulder was Jean-Hubert Martin’s “Les Magiciens de la Terre” (Magicians of the Earth) in Paris in 1989. –Within these 30 years, I myself faced a lot of changes, as well.– And this was the first attempt of an exhibition to subvert the Euro-Centrist view or this idea of superiority in the field of artists and artistic representation.

[R & D]

KB: ifa was founded in a time when transnational questions were not as developed as today. So, of course, it had a different agenda then. And, actually, we all a different agenda then. And I think these two exhibitions, “Riots. Slow Cancellation of the Future” and “Contemporary Photographic Art from Moscow” underline this development of these 20 or 30 years very well.

ST: I think so, too. At ifa, there was a shift in the directorship. Barbara Barsch who you worked with left in 2016 and Alya Sebti took over who then invited Natasha Ginwala to curate one of the exhibitions in the series Untie to Tie. So maybe Dmitry, you could talk a little bit about your work, also as member of a collective –you co-run Rosa’s House of Culture–, and your understanding of cultural work and cultural exchange. How have you experienced ifa’s approach to cultural work and exchange, besides participating in this exhibition?

DV: Thank you! After Kathrin talked, I feel very nostalgic. It was a very legendary time … when you really needed to establish contact … travel… especially with all this online activity right now. I remember very well ifa from my first visits to Berlin. I really appreciated it. ifa played a very special role as Kathrin also explained. Many things that were not possible to realize in a local context somehow were realized at ifa: a Belarussian show, a Ukrainian show. It was quite interesting. We can also speculate on a certain colonial type of approach, when you extract a certain kind of knowledge and position. But at the same time, from a local perspective, it was a mutual benefit.

[R & D]

DV: Absolutely, it was maybe the only chance to see a certain type of very interesting research on different situations in Latin America, in Eastern Europe, in Africa… to see very important installations and new voices that may later spread around international lines of communication. And also the information and the knowledge collected through these exhibitions come back through catalogues or dialogues between people that went to the opening. So the role of ifa was very important for these particular countries that had a certain problem with developing a contemporary art scene. Our experience was quite limited but we knew Natasha. It is always a pleasure to participate in these kinds of shows. You also correctly mentioned that a certain kind of shift from a national representation to a more thematic or curatorial representation happened at ifa, [that presented] a lot of voices that are not very present in the international or in the Berlin/German situation.

[R & D]

DV: I used to live and work in Germany, as a curator, producer, in Frankfurt and Berlin. We, Chto Delat, worked for a long time without a gallery but then found our home at KOW Berlin, which we are very happy about and which brings with it another type of relation to the art world. At the same time, Berlin is one of the few Western cities that is so well connected to the East, to Russia, to Poland… Vienna [is more connected] to the Balkans but Berlin definitely more to the North. And there is a historical knowledge and expertise, like Kathrin who perfectly speaks Russian and travels a lot. Many people commute between Moscow and Berlin or St. Petersburg and Berlin or Kaliningrad – whatever. Berlin is a super important place. And at the same time, I would say, because of this historical knowledge we are perhaps still most exhibited in Germany. They really understand who we are because sometimes this process of translation is very difficult. Actually, in that context ifa has always been very interesting because it was always a procedure of translation.

ST: It was also one of the very few West German institutions that focused on the Eastern landscape after the systems collapsed in 1989/90. That was also quite unusual at the time. I also wanted to ask, Kathrin, how your interest in Russia came about. You obviously speak fluently, as also Dmitry mentioned.

KB: This is a very banal story. I grew up in Hagen, in the West of the Ruhrgebiet or close to there. There was a school that offered French or Russian as a third foreign language after English and Latin. I decided to study Russian in school when I was a teenager. There was always this idea of the Russian enemy and the evil Ivan that invaded … and so on. I wanted to know the language and I wanted to escape the hegemony of the United States or whatever teenage idea I had.

[R & D]

KB: I then studied art history and Slavic languages in Bochum. There were Karl Eimermacher and Georg Witte who were very important. They both worked at the Slavic Institute and introduced me to what was called Inofficial Russian or Soviet Art. They also introduced me to Moscow Conceptualism at a very early stage, in the mid 1980s. That was the starting point. And then in 1989 with a grant of the daad I went to Russia to prepare my Masters on Soviet Socialist Realism. I was supposed to stay ten months but times were so exciting that I stayed for two years. This stay in Russia and the connections I had there and this huge interest that existed at that time in Russian contemporary art from Western museums and so on were my door opener for a curatorial career. For quite a few years I worked in the exchange between Russia and Europe, Russia and Germany, and also the United States. Today I have a bit of a different perspective on that time, when I see that this interest in the Russian art scene was a step of foreign cultural policy of the West. I see today that Russian artists were most probably instrumentalized to overcome or to make a decision in the last battles of the Cold War.

[R & D]

KB: I think that Chto Delat (What is to be done) is an exception from the rule, having quite a presence in Berlin and in Germany and also in an international art system, from a Western perspective. Berlin always claims to be this bridge between East and West and so on. But when you have a look at the Berlin art scene now, Russian artists with the exception of Chto Delat left very little footprints on that map. A lot of artists live here when we think of Vadim Zakharov, Dmitry Vrubel oder AES+F or… they all live here but they leave almost no traces in the institutional art or gallery scene. This speaks to the fact that this interest in Russian art tended towards zero after the Cold War ended.

[R & D]

KB: I think this is still the case. When you look at Blockbuster exhibitions like the Venice Biennale or documenta I still feel that Russia and Eastern Europe is highly underrated.

ST: Could you respond to that, Dmitry?

DV: Yeah, it’s very bitter but at the same a correct remark. I completely agree. But at the same time I think it was also the problem of the development of the Russian public sphere and democratic space, which was not able to create their own institutions. Contemporary art stays incredibly marginalized and criminalized. And right now, May 2021, I would say the situation is the worst I ever remember. It is super fragile. It started to escalate in December after Navalny returned from Germany to Russia and then everything started to collapse immediately.

[R & D]

DV: Without strong local institutions you can hardly participate. At the same time, you can also hardly move forward inside of this repressive bubble. There aren’t many chances to develop an artistic language that would be challenging and bring attention. Our case was quite different. We are explicitly international because we know this language but at the same time we manage to make serious artwork based on our tradition.

[R & D]

DV: Maybe because we all have certain experiences –I’m speaking now as part of the collective Chto Delat. Most of our members have serious experiences of living and working in the West but consciously decided to continue our work in Russia. This position of a mediator and a translator, not only of Western experience, but into Russian and vice versa, is really still quite exciting.

ST: Do you feel that institutions like ifa that organize cultural exchange are still as important as they were in the early 1990s? Or are initiatives like what you are co-organizing, Rosa’s House of Culture, something that focuses on the locale possibly more efficient in a climate like this?

DV: It depends on what you call “efficient.” I don’t like this word. What we are doing here [in St. Petersburg], is very local work, which must be done. Unfortunately, it should be done on a much bigger scale. At the same time, right now people are becoming more sensitive, who is speaking, for and with whom – the conditions of participation, that kind of ethical turn is very important. I also agree with you, with what you said, that ifa has to change its politics because you can’t simply continue this purely representational [approach]. At the same time, I also wouldn’t undermine it because for many people to have that expertise from the outside [is important] – as Benjamin always said, that to understand something you need to distance [yourself from it]. But who creates this distance? How is it structured? Who profits from it?

[R & D]

DV: What Kathrin said that looking back, she understood how art was instrumentalized in the post-Cold War relations… Now, we have a new Cold War. And which side are you on? We are openly dissidents. Kathrin understands me quite well, I think. When I reflect on the current situation I think that we are dramatically returning to this condition of dissident production. And dissident production was always somehow very marginal and local and at the same time has a value internationally. It was the only source to continue to have certain resources and visibility. At the same time, the situation is not like in the 1980s. We have institutions, new ones like Garage or VAC. They are doing serious work and they belong to the most powerful institutions internationally. But there are very few. And they also have a certain limitation because right now self-censorship is incredibly high. Everyone knows what you can talk about and what you can’t. And the rules of the game change every two weeks. People get scared about how to continue because business and power in Russia are intertwined so you can’t be incredibly independent. Most oligarchs, private businesses, absolutely depend on the [political] condition in order to survive.

[R & D]

DV: It used to be that after 2014, for example, there were heaps of Ukrainian shows. Where are they now? Right now, the focus is absolutely outside of the East. It’s on the decolonial, the post-colonial, which is legitimate, absolutely. But at the same time, I would dream of a world built on more equal forms of partnerships and resources.

ST: I totally agree with that, Dmitry. Thank you so much, Kathrin. Thank you so much, Dmitry, for sharing your thoughts and memories of ifa with us. This seems like a good moment to end this conversation as we are also running out of time. I’m very grateful to have had the pleasure to talk to both of you… and I hope that the listeners enjoyed this conversation as much as I did. As mentioned in the intro, please also check out the bonus track to this episode, produced by R&D whose song “Bendable” accompanied this conversation.

Please also stay tuned for two more episodes in this series Past –> Present that we are currently planning to broadcast in the early and late fall of this year. Until then, enjoy the summer… and I hope to meet you back here in a few months.