To celebrate 30 years of ifa Gallery Berlin, this podcast brings together artistic and curatorial positions associated with the gallery since its founding in 1991.

Using the gallery’s program as a reference point, selected guests converse with Sandra Teitge about its thematic focal points over the last 30 years. In contrast to many West German cultural institutions of the time, ifa Gallery Berlin concentrated early, throughout the 1990s, on collaborations with artists and curators from Eastern and Southern Europe. How have artistic approaches, curatorial practices and working methods changed over the years? And what is the situation regarding public space, which historically has been more actively incorporated into artistic practices in Eastern and Southern Europe? Does it still provide scope for action in the region? The podcast links these and similar questions to wider contemporary issues and gives a voice to local artists and cultural practitioners.

For the second episode of Past –> Present, Sandra Teitge speaks with Berlin-based curator, writer, and educator Övül Ö. Durmusoglu and Vasif Kortun, one of the most influential figures in the Turkish and, in fact, international art and cultural scene. The two of them will converse about their respective work with and beyond ifa in Germany and Turkey; their exchange is accompanied by an audio contribution by the Berlin-based musician and artist Banu Çiçek Tülü.

Concept: Sandra Teitge

Music: Kolbeinn Hugi

Sound editing: Kolbeinn Hugi

Thanks: Ev Fischer, Stefano Ferlito, Inka Gressel, Susanne Weiss

Welcome to Past –> Present

I’m Sandra Teitge, Berlin-born and based curator and researcher, and the moderator of this podcast.

Past –> Present brings together artistic and curatorial positions associated with the ifa-gallery since its founding in 1991. Using the gallery’s program as a reference point, I will converse with a group of guests about ifa’s general ethos and research interests in the early 90s and today.

What’s the relevance of cultural institutions that foster artistic & cultural exchange, such as ifa, back then and now (especially in times of rising nationalism and cultural isolation)?

In contrast to many West German cultural institutions of the time, the ifa Gallery Berlin concentrated early, throughout the 1990s, on collaborations with artists and curators from Eastern and Southern Europe. How have artistic approaches, curatorial practices and working methods changed over the years? And what is the situation regarding public space, which historically has been more actively incorporated into artistic practices in Eastern and Southern Europe?

This podcast links these and similar questions to wider contemporary issues and offers a podium to artists and cultural practitioners affiliated with ifa at some point in their career.

Today, for this second episode of Past –> Present, I’m very happy to welcome and give the floor to Berlin-based curator, writer, and educator Övül Ö. Durmusoglu and to Vasif Kortun, one of the most influential figures in the Turkish and, in fact, international art & cultural scene who is talking to us from his home in a sea-side town along the coast of Turkey. The two of them will converse about their respective work with and beyond ifa; their exchange is accompanied by an audio contribution by the Berlin-based musician and artist Banu Cicek Tülü, also available as a bonus track.

Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu lives and works in or, rather, from Berlin. Her interests lie in the intersection of contemporary art, politics, critical and gender theory and popular culture. As a curator, she acts between exhibition-making and public programming, singular languages and collective energies, material and immaterial abstractions, worldly immersions and political cosmologies. Her most recent curatorial projects are the 12th Survival Kit in Riga and the 3rd Autostrada Biennale entitled What if a Journey… that ran from July to mid September of this year in Prishtina, Prizren and Peja (Kosovo).

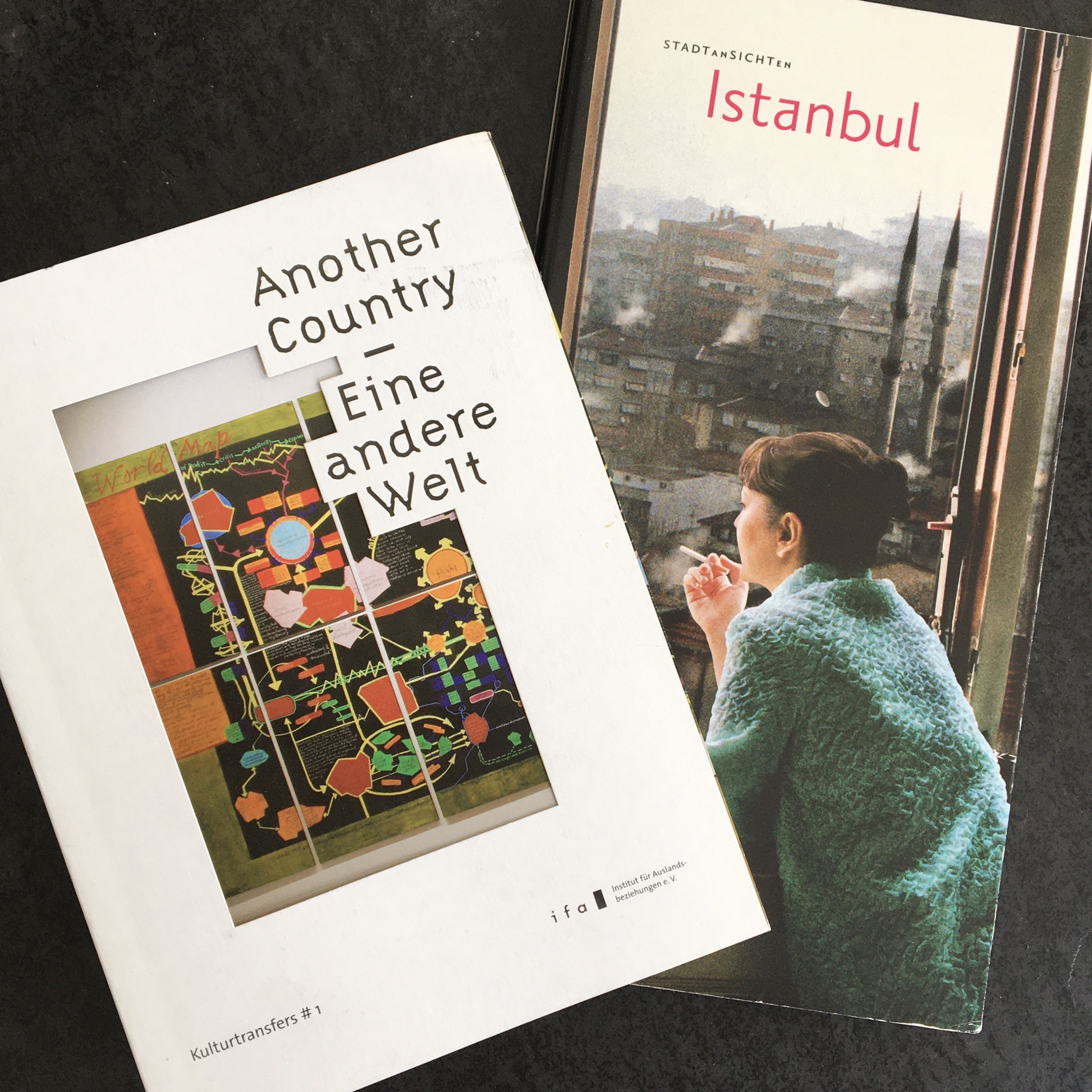

For ifa, Övül curated the group show Another Country | Eine andere Welt in 2010, an exhibition in the frame of the series Cultural Transfers, which was an exploration of the migration of forms, contexts, and artistic strategies. It was her introduction to Germany and its cultural scene where she subsequently decided to live and work and simultaneously the beginning of her research into the exilic position.

Övul will be conversing with Vasif Kortun, described as “an unabashed power broker” in the Istanbul cultural scene.

Vasif is a curator, writer and teacher in the field of contemporary visual art, its institutions, and spatial practices. He is currently a research and curatorial advisor to Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha and, in the past, was the founding director of Research & Programs of SALT, an interdisciplinary cultural institution based in Turkey with innovative programs for research and experimental thinking.

He was also the founding director of a number of institutions including the Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center, İstanbul Museum of Contemporary Art and the Museum of the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, in the United States.

His projects are too many to list; Vasif has worked on numerous biennales including Taipei Biennale, the São Paulo Biennial (1998), and the Istanbul Biennial, for which his 2004 ifa-exhibition entitled STADTanSICHTEN. Istanbul (URBANreVIEWS), an exhibition as part of the series URBANreVIEWS, was actually one of the stations or testing grounds for this upcoming 2005 Istanbul Biennial. It focused on individual megalopolises from the perspectives of urban planning, sociology, communication and aesthetics, and took into account the respective cultural landscape.

Banu Çiçek Tülü’s practice navigates between sound, music, research and activism using DJ’ing as an artistic form. Born in South-East Turkey and based in Berlin, Banu’s illegal rave experience defined her taste in experimental electronic music – mainly techno. She believes in the political possibilities of sound and music, and utilizes both as an empowerment tool for different communities and minority groups. Banu has been supported by Musicboard Berlin and is a fellow in the Namibia Program at Akademie Schloss Solitude, Stuttgart/Germany where also Övül was a fellow – many years ago.

***

ST: Welcome both of you to this podcast. Thanks for joining. I’m very happy that this worked out. You are both back at your respective homes after being in Kosovo together, actually, last week. And you both also saw Övül’s exhibition, which we can talk later a little more about perhaps. First, since this conversation is connected to ifa and the exhibitions that both of you organised and curated there a few years ago, let’s start by talking about those two shows to give people a little bot of context. So, maybe, Vasif, you could start with explaining when it took place, who was involved, also from ifa’s side, how it got there, what the experience was.

VK: It’s a good question. It was so many years ago but I can still imagine a trajectory that led to that exhibition because I was working on Istanbul, the city and the city practices, and the transformation of the city, as well. And it started with an exhibition in 2001 at Proje4L, which was Istanbul’s first contemporary art museum or Kunsthalle type institution. At the time it was called Becoming a Place.

ÖD: I remember that exhibition very well. It was a very important exhibition for me, too.

VK: Oh yeah. Good. Thanks. And then, after that there was, along the way, that exhibition in Stuttgart and Berlin. And some artists of the Becoming a Place exhibition also took part in this show like Erik Göngrich and Seçil Yersel – but not all of them. I didn’t curate the exhibition by myself as I recall; I did get some support, assistance, and help from Pelin Tan and a few other colleagues. And then, eventually, in 2005, it led to the Istanbul Biennial whose name was Istanbul. So it was kind of a station on the road to test things out and to see how it works. I think I installed the Stuttgart version but I don’t remember installing the Berlin exhibition, actually.

ÖD: Maybe it was installed in Stuttgart and then travelled to Berlin and the team in Berlin installed it according to your instructions, most probably. Because mine was like that. And I used the occasion to come to Berlin. I was still at Akademie Schloss Solitude for a residency so for me it was easier.

ST: So maybe you can talk a little bit about your show, Övül?

ÖD: Sure. The exhibition Another Country / Eine andere Welt was actually the reason I came to Germany in the first place. I was doing research, a trainee ship at the Dia Art Foundation in New York working with Lynne Cooke. That was finishing and I remember the proposal that arrived from ifa. And I managed to come at some point in between to see Stuttgart and to see the residency, if I would like to get it or not. [So shortly] after that I [organized] the exhibition [at ifa] when I was in Stuttgart doing the residency at Akademie Schloss Solitude. This was also an anniversary project for both of the institutions. And I used the occasion, basically, to relocate to Berlin, when the exhibition was moving to Berlin. And here I am, on and off, still in Berlin, somehow.

ST: How many years later?

ÖD: 10 years later, I’m still here, somehow. I travelled all around. And, of course, I wasn’t in Berlin all this period. But [the ifa show] was my introduction to Germany. I never thought I would have worked in Germany or that I would have chosen Germany as my base in Europe.

10:17-10:44 SOUND

ST: Great. And, Vasif, you hinted at the fact that [your exhibition] was a step towards the Istanbul Biennial and the idea was also to bring Istanbul’s public space into Stuttgart and Berlin’s gallery space, right? Övül, you just recently finished working in public space with the Autostrada Biennial. So maybe we could talk a little bit about this notion of “art in public space” and how you approach it in your work. How has it changed over the years, especially in Istanbul. Vasif, you have worked so extensively in the city, many times, within institutions but also in public space. Maybe we could talk about that.

VK: That’s a good question. Maybe Övül can answer that so much better than I can. I don’t start with questions of public space or gallery space or exhibition space. Those are not the a priori concerns that have ever been of interest to me. I should be very clear about that. I start with the problem first and then try to see if it’s for public space or for the gallery space or for the digital space or it’s an archival project or a book or a publication or whatnot. And also my failure in dealing with these projects is that I have a problem with commissions. I like to do things when I really like to do them. And with commissions most of the time I really fail. There is something missing. There is something that just doesn’t work well. If somebody asks you to do an exhibition, you are like “yeah, ok”…

ÖD: Maybe to continue the thread that Vasif is following I would say that is also a little similar to me. Because in my practice I work more with publicness than with ‘art in public space.’ My concern is more about notions of publicness and how they differ and where are the conflicts that are happening. I’m actually interested in that most of the time. And sometimes it happens in city spaces and sometimes it happens in the galleries equally, in institutional spaces. So also the concern here for me is more about the publicness and the free space and the notions of democracy at the same time, in the very background, in a more general framework. Also in an unexpected way, the first project I realized before naming my work as curatorial work was inviting visual artists to exercise street art practices in Istanbul and about its exotic identity and it was called Exocity. It was a very beautiful exercise for me that introduced me to contemporary art curating. And so the road follows. Also in that project I was inspired by Becoming a Place. I was inspired to see the conflicts of public space and how it can be broken in different ways.

SOUND 14:51-15:47

VK: The discussion, of course, is context-bound and situation-specific. In a way, I would be very pressed to call Istanbul’s outside spaces public spaces. The terminology doesn’t even exist in Turkish. We have different words that we use for ‘public space’ but they all have legal frames rather than ‘publicness.’ Of course, it’s never a given. Each time it, [public space] has to be invented and re-invented and re-inscribed. That’s for sure. At the same time, the Turkish situation, as probably in most Muslim societies, too, if I could make a broad generalization, from Palestine to other places, the notion of public space is wrought with problems. In Turkey, a university campus, for example, is not a public space. So we can go on and on with that. So what we are dealing with always is other kinds of issues, very specific kinds of issues dealing with what ‘public’ constitutes.

ÖD: Just out of curiosity, may I ask if you remember the experience, how did it feel for you to place such a research at that point in Germany about Istanbul? Because you were taking a very particular political position. This [research] was also introducing a different political position [with regards] to the notions around Turkey in Germany, as well, let’s say. If you could say a few words. I would be very curious to hear [more about] that.

VK: I wasn’t thinking of Germany to be very frank with you. I know Stuttgart a little bit. I’ve been there a hundred times or so because my father was working for a charter plane company that flew Turkish workers between Istanbul, Izmir, and Stuttgart. So I was quite familiar with the strange airport, the bags of the workers, the negotiations of the everyday etc. Stuttgart for me was a place to learn, to see art. It may not be for other people but there was that kind of museum, that lineage of museums, on the other side of the street. All of that was very important to me. So it wasn’t ‘Germany, Germany’ that I was thinking of. Also it wasn’t Turkish-German citizens who were living in Stuttgart that I was thinking of. I find that, especially in our days, the 2000s, it is a preposterous idea to imagine that you would get Turkish [visitors through an exhibition like mine]. It would have also been abusive notion [in general]: you get the Turks when there is a Turkish exhibition and then next month is Chilean [artists] so you try to get the Chilean workers. And I find that in European institutions to be systemically abused. It wasn’t in the Stuttgart case, certainly not. There wasn’t such a premise and we weren’t fed Döner Kebaps at lunch or dinner. So that was very nice. Nobody was trying to make you feel in…, you know, all of that. It was just the end of those days. Just to come back. Perhaps if I can tie it to another story. Övül, you know it very well. I think you know this story.

SOUND 20:02-20:32

VK: In 1990, I went on a tour of Germany with a huge package of artists from Turkey in my bag. It was before I started to make exhibitions. And the idea was that there are some great artists and whatever artists in Turkey, as well. And ifa was one of these situations on my horizon. And at that time I could not even get a meeting. I wasn’t let in the door of ifa, basically. And that had a very bitter feeling at the time for me. I was vengeful; I was angry. They were not doing their work [in my mind]. This was also two years before I curated the Istanbul Biennial. And to tie these two things together: at one place I wasn’t able to get a meeting; in the second place, which was the Istanbul Biennial, Germany offered me an artist, an important artist, of course, which had nothing to do with my exhibition concept, with my brief, with my discussion etc. So I said, also with the ifa story in the background, “sorry, you are not in the exhibition.” And imagine, a country like Germany being told to go away from the Istanbul Biennial. That was that. But we had to level with the situation and that’s how you level with the situation. I don’t mean that it’s a colonizing approach but it’s a very West-European style of teaching other people of how they should act and behave and what they should like and not. Things that come out of good packages and good boxes always are put up without question – and that’s what you get. That’s what Beral Madra had to deal with in the 1987 and 1989 exhibitions… and all the exhibitions from 1974 onwards within the context of the Istanbul Foundation for Culture that later did the Biennial. Things came out of boxes. You never had an idea. You were never allowed to have an idea. So in a way that was that. Things happened. This kind of levelling is good because it sets for a more appropriate proper relationship for the future. It didn’t help me but it helped the future. So anyway, it was 1999 that Iris Lenz came to a small institution I had founded in Istanbul. It was called ICAP, Istanbul Contemporary Art Project, which was basically a room, two rooms, but it was quite a tiny place. It was one of the initiatives that I ran in those days; I did some publishing and all kinds of crazy things… and they came. ifa came to my door. I said, “That’s it. Now we can talk. Now we are even.” And of course I welcomed them. That’s how the relationship started and developed. But that is [also] the story of another time, obviously. It has all the markers of a different period. It doesn’t apply today. We are way beyond that.

ÖD: But it’s also important to remember where we are coming from and the issues and the questions that were dealt with by the previous generation in order to come to the questions we are having [or dealing with] today.

VK: Exactly. It sounds banal today, even the whole story. Because it is not as sophisticated or it doesn’t [involve] the sophisticated questions of today. It is more fundamental.

ÖD: But Germany and Turkey, of course, have this particular relationship, in terms of cultural networks. Germany has always been the place where a lot of contemporary art from Turkey has been shown. Of course, there is also the position of Rene Block who came and did extensive research and helped many artists from Turkey to become international artists. So that internationality passed through Germany. There is always this interesting relationship, not only the Gastarbeiter question; there are various levels, various phases of cultural relations between Turkey and Germany. This has been also kind of critical. Before France or Belgium or the Netherlands, it was Germany [that initiated] crossovers, encounters. Of course, that was also the reason for why it was important for me to accept the residency and to come and work in Stuttgart, start in Stuttgart and to develop the exhibition that I did departing from James Baldwin’s novel Another Country – imagining another country. It was a point when I had already moved from Turkey for my own political reasons and I was looking for another country myself. And when I read James Baldwin’s novel in New York it touched me very deeply. And, of course, it was a novel that was finished in Istanbul. That was my connection to the ifa exhibition, also looking at previous exhibitions and programming so far –I came in a time when there was a different direction and different projects with Elke aus dem Moore– I really wanted to bring in this concept of creating another country in a country that we are taking our work to, where we can hear each other and where we can love. That’s also one of the things in James Baldwin’s novel, as well, with a very heavy Black struggle background. And why I decided to go for a very diverse group exhibition, it also has been one of the first exhibitions [of this kind] at ifa, in the ifa galleries. I wanted to break with [this approach of] someone coming from a [specific] region and always deal with this [very] region or come with the questions of this region. That was on my mind very clearly when I was devising the show. I wanted to break the prejudice before the prejudice arrived.

SOUND 28:30-29:00

ST: To look at ifa’s side of this conversation, it is definitely true that the whole approach changed over the years. And we were also talking in the last podcast with Kathrin Becker and Dmitry Vilensky about the fact that because of the time, because there wasn’t Internet everywhere and not everyone was able to research so broadly and internationally that the approach had to be more of a step-by-step one: going to one country, research, and find artists etc. So everything was much slower. So all these factors played into this fact that in the end there were these more ‘national’ exhibitions. But now with the new directorship of Alya Sebti [ifa gallery Berlin], for example, it’s become a very different dynamic.

ÖD: Yes, it’s beautiful to see. But as a I said, it was not necessarily that the prejudice was expressed or done; it was more for me to really create that position as someone coming from a stigmatized country, in Germany – there is this complicated relationship; it’s a bit different than with other countries. And also there is something still going on in different cultural institutions that one is expected to work with Turkish artists only or to work with diaspora problems constantly; these kinds of projects are supported with general funding. This is a question that I have been raising for quite some time in Germany, working internationally in Germany, what does it mean to be in such a position and to be able to claim a different cultural and intellectual ground, a little bit like creating an awareness about these set of rules that are almost invisible but working constantly. And, of course, things are moving on and are evolving in very good ways, and also are part of education, so [therefore] structurally. Now in UdK and Braunschweig, for example, I see the discussions and questions that are being raised. They are very important questions that institutions are asking themselves and I see it as very very healthy.

VK: That’s so true. It’s interesting that in a way, the idea of it being stigmatized does not an outside interference. You approach certain situations with that stigma even if the person in front of you may not have that approach. It has been what it is. But then again, I would imagine that the frame of a country is a frame as good as any other, in a way [for an exhibition]. I wouldn’t uphold this argument. But I’m saying it just for the sake of our discussion. We are never outside our time. But what are the misgivings of the present? What are we missing now? What are we overlooking at this moment? What kind of power networks are we plugged in and can unplug from etc etc. I think those are legitimate questions to ask again. But I agree with you. For me, these exhibitions that I did outside were not for me, there were for the artists. Because I spent so many years, before I returned to Turkey, outside to establish myself not as a person from Turkey but as who I am. Then, I went back to Turkey to use that leverage. I never wanted to be the ‘agent from Istanbul’ etc. etc. That was at the time a hard role to take. Because it happens that you become the ‘person from Istanbul.’ But it was never my intention.

ST: Vasif, did you always know that you would want to go back to Istanbul or to Turkey and work in situ and establish institutions there?

VK: You know, I work in my own little world, my own mind. I was offered documenta twice and I turned it down both times. Because I’m not interested in making big exhibitions outside of the country [Turkey]. I really wanted to go back because I wanted to start an institution –and it took a long time to start– with a research component, with a great library, with all the things I missed when I was growing up. [An institution] that we could build a new situation, a new ecology for the younger generation. This sounds very cheesy right now but that was my big ambition, to have a great library, great archives. It was a no brainer. I got offered to become the director of the Boston ICA and the same night, me and my wife we decided to go back to Istanbul. Because if I had gotten into that kind of operation, I would have never gotten out of it, you know. And that would have not been a life worth spent for me because I am really devoted to Turkey. That’s why I’m also not leaving it now with all the reasons to leave this goddamn place.

ÖD: But I also do think, I may be mistaken, but I see the generation that constructed the cultural spaces of Istanbul in the 1990s, in the 2000s, had a similar ambition, with all these different figures. They wanted to come back and invest in the city. They wanted to create another Istanbul. It was possible for a long time. It is just receding to another horizon now. But it was there. From my side, I feel very lucky to have grown up with that when I was studying at university in Istanbul. It contributed so much to my personal horizon and my view of the world. And it’s interesting to see today how the things we take for granted today is thanks to those before us who decided to come and to construct these grounds; it is such a luxury from the position of today. It’s interesting to see that, also, how certain things have their time and they create this very memorable effect; those 20 years in Istanbul are quite memorable.

SOUND 36:55-37:38

VK: The generation that was able to do this kind of work was not exiled. They were not exilic. They were not forced out of the country with people chasing them out. [People were] being chased out after 2016 or 2016 was the closure of all possibilities hence is the reason for so many artists and colleagues [leaving]. [It is] a new generation, the generation that comes right after you, Övül. So the situation has changed a little bit but the exodus is quite real and I don’t know what will come out it. Right now, it looks very depressing because they are stuck in a time [capsule] of 2016 and we are already in 2021. But the exilic is always stuck in a time [capsule], unfortunately. That’s what happened to Turkish artists in Germany in the 1970s. They were also stuck; they were ghetto-ized. The new ones are self-ghetto-izing.

ÖD: Exactly. It’s a kind of comfort-zone behaviour that kicks in, without intention. It’s really happening.

VK: It’s a great project to do, a new project for ifa!

ÖD: One also needs to say that [this discussion] touches on the general situation of the world, how [in general] the balance is functioning. There are certain countries that are rendered impossible. And they don’t deserve it. As we see today with Afghanistan, as an extreme example. It’s part of that operation that forces a lot of artists and cultural workers to come and live only in certain [cultural] centers. And they are able to do that only now. I think Berlin has now a scene that developed out of this. You see all of these different migrant communities that are coming to establish themselves here, for example the Arabic-speaking population, that never existed in this way [and is] culturally and politically very active and very visible. And, of course, also this new generation of artists from Turkey with a different voice, with different concerns, with a different profile.

VK: Are they talking to each other?

ÖD: Sometimes. But not all the time. I think these conversations will take longer [to develop.] I think there are stronger ties amongst the Spanish- and Arabic-speaking communities as far as I see. But this the situation, really. I have also been discussing this with another colleague of mine, Ana Teixeira Pinto, who is from Lisbon and who has lived in Berlin for a very long time, that this is the situation. We may like to work and live back [in our cities or countries] but we don’t have the space to exercise our visions. There aren’t spaces as such [there]. So it is the [Berlin cultural] scene that we are giving the best we can and receiving responses or trying to get better responses.

ST: Spaces are also being founded in Berlin that support these communities.

ÖD: Exactly. There are different forms of solidarity models that are growing very strong. It is not about that. It is more about how the balance in the world culturally functions towards certain centers and that the places where these exilic communities are coming from cannot be invested in culturally. Certainly, that can be said for Egypt. Trying to constantly exercise their voices to defend their communities back in Egypt. It’s an interesting panorama. Culturally, it is giving a lot to Berlin. And [the city] has never has been so plurivocal. That was always my hesitation after realizing the [ifa] exhibition. It was too white for me to stay so I always tried to get out. But at a certain point I also realized the there is a new scene growing that it is much more plurivocal, with different concerns creating their beautiful experiments and confrontations. So that’s how I decided to stay.

SOUND 43:11-48

ÖD: The artistic community, for example, that lives in my neighborhood for example but that never speaks to each other because of the way we are all working inside but always outside the city; how to come back to each other and remember our collectivity with all of its problems and all of its concerns. It’s not a fully rosy picture. But it’s very important to attempt it, especially when publicness is gaining a new meaning though the pandemic and through the digital conversations we are having. Of course, it’s another excess towards the world. But still, in our places where we are living we need to remember to talk to each other in a much more straight forward effort and also, to claim the streets. It’s always very important to claim the streets.

ST: And to [slowly] wrap this up –I know this is a very interesting conversation. Maybe this is exactly what institutions like ifa can do, to provide a space without having an agenda, to create a neutral space for these communities to come together. I worked for the Goethe Institut and ifa and Goethe are somewhat related. And the Goethe has managed in situations that were very dramatic, like in Beirut during the Civil War, to provide these spaces for people to either find shelter or to come together as a community. That probably is the best future scenarios for institutions like ifa.

ÖD: I agree. And coming back to the beginning of the conversation, to really undo and unlearn those existing baggages that are coming from Western institutions because they didn’t disappear; they are there. But, of course, all of these forms of conversations and where they are taking us make institutions leave more of these baggages behind. But there is still work to do there. It doesn’t matter whether its name is ‘decolonial’ or not. It’s important to leave these baggages behind.

VK: And structurally.

ÖD: Yes, structurally

ST: Most importantly.

Thank you both very much. Thank you, Övül. Thank you, Vasif. OUTRO As mentioned in the intro, please also check out the bonus track produced by Banu Cicek Tülü of which fragments accompanied this conversation. Please also stay tuned for one more episode in this series Past –> Present that we are currently planning to broadcast in early winter of this year. I would like to thank Inka Gressel and Susanne Weiss for the invitation, Ev Fischer and Stefano Ferlito for the general support and Kolbeinn Hugi for post-production and additional sound. I hope to meet all of you back here in a few months.