Historian, teacher and activist Claudia Andrea Gotta and artist Karen Michelsen Castañón discuss aspects of the exhibition related to the histories and struggles of the collectives involved in the exhibition.

K: Welcome to this podcast which we will use as a space together to discuss issues stemming from the show La escucha y los vientos at ifa Gallery in Berlin. Today we are here as a result of an invitation from the curators of this collective project, Inka Gressel and Andrea Fernández. My name is Karen Michelsen Castañón; I am an artist and cultural worker in Berlin. Within the system of prevailing structural racism here in Germany, I am a person of color, though in Abya Yala I am a white mestiza person. Claudia, thank you so much for being here.

C: Hello, everyone. My name is Claudia Andrea Gotta, I am an Argentinean educator, teacher, historian, environmental educator and activist in the field of human rights and specifically for the rights of Indigenous peoples. At this time, in addition to my work at the University, I am a national secretary within the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights, dealing with the rights of Argentina’s Native or Indigenous Peoples.

K: Thank you Claudia. I wanted to tell you all briefly the story of how we met, because I’m in Berlin, and you’re in Rosario, Argentina. I had the pleasure and honor of meeting you in Rosario in 2019, when I interviewed you for the audiovisual project No más poemas para Colón [No More Poems for Columbus]. Each person interviewed recounts how the myth of the so-called discovery of Abya Yala has been constructed in their own territorial and historical context and how it connects to the realities in which they live. What I found interesting when we talked to begin thinking about this podcast was that both Germany and Argentina are still constructed as homogeneously white nation-states. The histories of the Peoples that pre-existed these nation-states are made invisible and that is why the exhibition is so interesting, because there are multiple collectivities of people who participate within La escucha y los vientos. Through their works, they alert us to their lives, their resistance, their struggles, in this particular case, in the territory called the Gran Chaco.

C: This exhibition is possible thanks to the involvement of a series of collectives including one we wish to name Radio La Voz Indígena

K: The ethnic memory workshop of the Aretede indigenous organization.

C: Also, textiles, bearers of messages from the Thañí / Viene del monte collective of women from Wichí communities, which in turn is part of the Lhaka Honhat / Nuestra Tierra association.

K: There are also the textiles of people from Wichí communities, particularly La Puntana.

C: And the ceramic works of the Chané Tutiatí Orembiapo Maepora community and many, many more people. Even more than that, Karen, there were countless people that it would be impossible to name who participate with this group and who have made this exhibition possible.

K: That is so true, Claudia, and for more information listeners can go to the same webpage of the ifa Gallery for the exhibition. The brochures are available there, and in each brochure each person is listed with their individual or collective contribution to this exhibition. So for this first podcast, I’d like to ask you a question: what historical issues do you think are important to emphasize in order to be able to support the struggles of the groups participating in this exhibition?

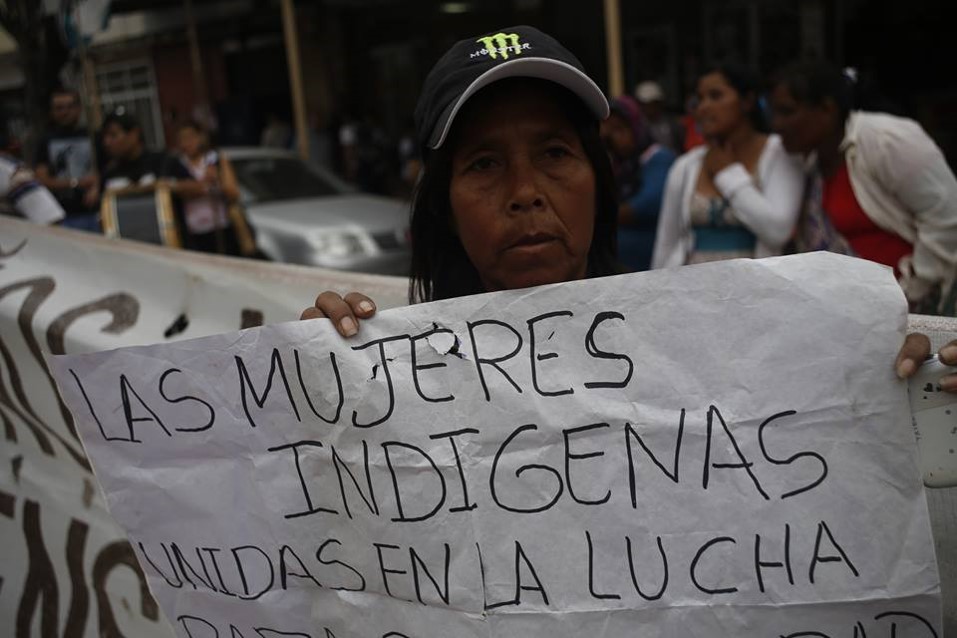

C: We could say that these Peoples—who have been invaded, trapped, cornered, or dispossessed of their ancestral territories—have a form of resistance in this play with words, of resisting in order to continue existing, that invite us to recover these other forms of knowledge and constructions from the community level. Their way of conceiving of the place they inhabit—from the furthest reaches of time in some cases or in others they have been relocated by the advance of the market and capital in their territories—show us a way of existing in the world that allows us to keep fighting, through the collective, and to keep putting into action their own beliefs and their forms of conceiving of life. We should recover these other forms of conceiving of life in consonance with multiplicity and diversity of life in the territories. As we are going to be able to see in this exhibition, in the material elements that carry these messages, the brush, the lake, the animals, the stories that are marvelously interwoven into the weft of the textiles that the women from the region of the Gran Chaco have placed into this show. They allow us to see just that, the continuous re-elaboration of their story, enacted in the present to retrieve many elements that behave like other types of values, as another ethic from and for life. An ethic in which women have a truly central and crucial role, and which in addition also invites us to decolonize feminism. The women of the Gran Chaco show us how they are both preserving and, simultaneously, recreating their own culture. Feminism in Abya Yala invites us to recognize that feminism must be decolonial or it will not exist at all or will provide nothing. This is because quite often we are building resistance in the face of concepts that are already colonized in and of themselves and then somehow this exhibition shows the people who visit it—and hopefully it will be physically open for visits soon, but if not, at least virtually—other forms of inhabiting territories, another conception of life made manifest in what are seen mistakenly as cultural artifacts in a more hegemonic vision. In reality, these are objects of daily life that have significant meaning and also concrete functions in the realm of the everyday, but what they center in the debate and in our thinking is how a culture recreates itself through these textile and ceramic manifestations, a vision of a world that we should not just recognize, but also from which we must learn. Because the urgency of these times demands it in order to be able to build a new way of relating to one another as the human community that we are, on different levels and in consonance with other manifestations of life.

K: Yes, thank you Claudia. Obviously, I believe that the history of the Gran Chaco cannot be summarized in a couple of minutes, but perhaps you can give us a couple of points of departure, recognizing that in Europe the process or processes of invasion that began in the 19th century are rarely discussed. This will give us a more historical perspective.

C: Yes, of course, thank you, I think it is a necessary clarification or necessary information, although in this format it will have to remain brief. The Gran Chaco that we refer to today as such in our country forms a much broader territory that includes other countries such as Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay. The Gran Chaco is a setting where the brushlands, the jungle, fostered forms of life for millennia that we of course know very, very little about, because this was conceived of from the hegemonic perspective as the other great desert. This hegemonic conception attempted to impose this idea of an empty space onto two great expanses of territory that the Argentine nation-state was finally able to incorporate later into the national territory. This process began for Abya Yala in the 15th century and arrived here in the last quarter of the 19th century with the existence of two large expanses of territory: that is, for Argentina, the southern reaches which would be called Patagonia and the Chaco. These territories were conceived of—mistakenly, but not innocently—as deserts, because the desert is constructed out of this sense of nothingness, of the absence of something that has another connotation and that, therefore, defied the gaze of the hegemonic class of the moment, the landowning oligarchy that wanted to advance on the territories still in indigenous control and to complete its “civilizing project.” In this sense, the idea of the desert is an oxymoron, a desert is an unconquered space. In fact, none of these areas was actually a desert; on the contrary, they featured and still feature an overflowing abundance of culturally diverse and divergent life forms that were far different from what the Argentine nation-state was attempting to impose with its vision of a monocultural and monolingual identity, which was clearly homogeneously white in its conception. Therefore, throughout this history that has been on-going for more than two centuries and almost two and half centuries, the state worked to construct an imaginary of these territories that has no resemblance to what had been gestating there forever and what is still in existence there now. These other perspectives and these other forms of inhabiting, other ways of creating culture and also, of course, other ways of conceiving of nature and life and, therefore, what is being taught, what should be taught is this preservation of knowledge that centers Wichí, Chané, Mocoví, and Qom women. There is a wide array of cultural diversity here and also linguistic diversity. These territories have great biodiversity and a great cultural diversity; nevertheless, in the hegemonic worldview, they are conceived of as places where poverty is registered by the colonial gaze. This gaze has created a gap in our way of seeing Other territories and Other brothers and sisters. So then, otherness is also something that must be dismantled and this notion of poverty since these are not poor groups but rather they have been actively impoverished. They have been impoverished within this evermore brutal, capitalist, hegemonic system that we have had over the last decades, a system that continues to advance upon these territories. We are going to talk about this in the subsequent episodes in other ways; nevertheless, we do not just have to take action—and this is what this exercise you have invited me into is dealing with, and I appreciate the invitation—but also to be able look at these other expanses of territory, toward other ways of inhabiting the world, and, of course, toward these other messages that are embodied in these cultural expressions that we alluded to previously: the textiles, ceramic objects and also the voices of the people who inhabit the Gran Chaco in Argentina. They transmit other messages to us that not only do we need to encounter, but also we must recover these messages and at some point internalize them, since—as I said before—they need them urgently.

K: So for now we’ll say goodbye and we hope to meet again soon to continue delving into other elements of the show. Thank you, Claudia.

C: Well, actually thank you, and see you soon.

Translation: JD Pluecker