The two artists’ full names are Eduardo Ponjuán and René Francisco Rodriguez, and they have been working as a four-handed duo, so to speak, since 1986.

Almost exactly five years ago, thousands of people besieged Dresden’s main train station to jump on the train full of embassy refugees coming from Prague. Today, the same thing is happening again in Havana. Hundreds waited at the port ferry docks to board and “divert” it to Florida. The patriarch’s autumn appears to be turning into winter.

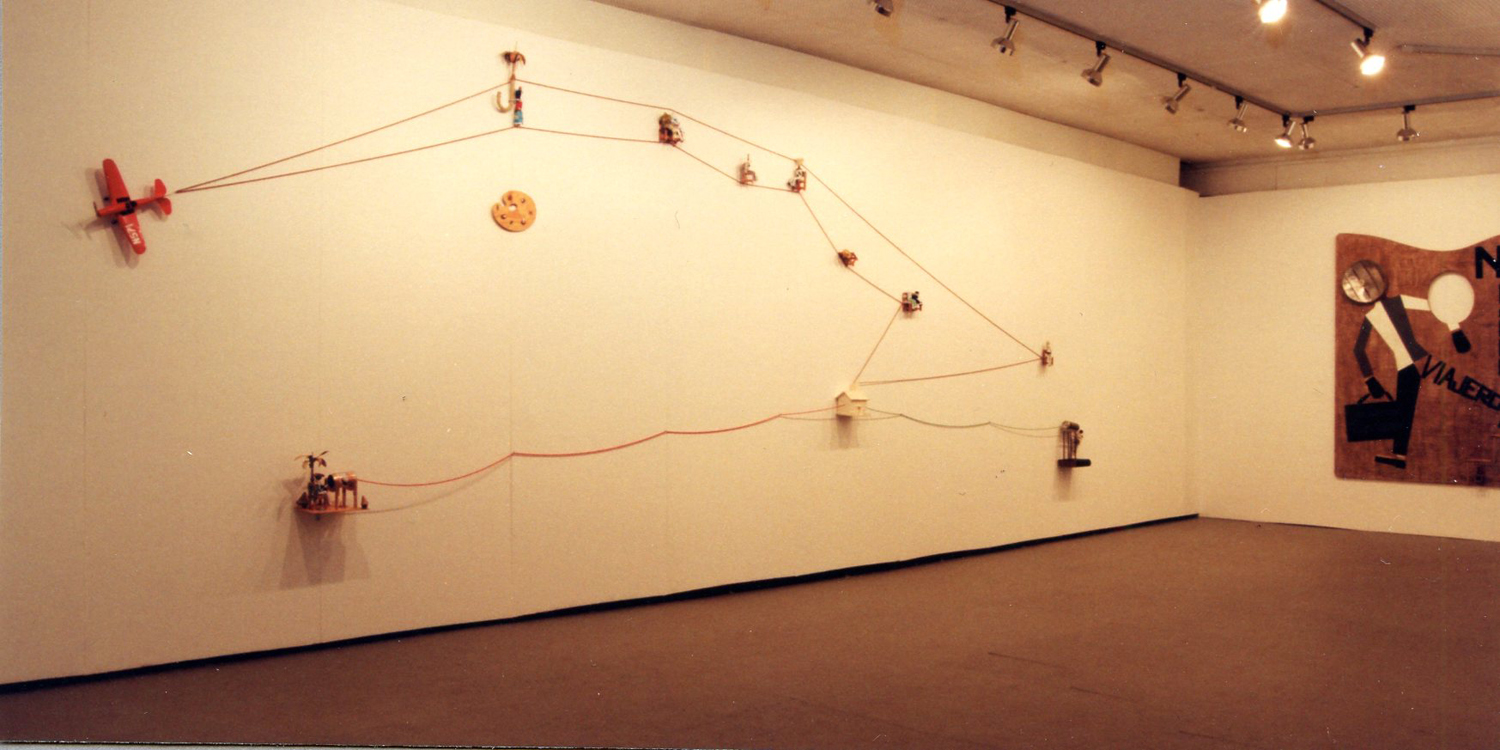

In this context, the exhibition of the Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen “Vuelo” gains explosiveness. “Vuelo” means flight and sounds like a promise to the ears of many Cubans. The two artists know this. But they certainly had more than just the most obvious interpretation in mind when they chose the title. They also understand it to mean flight as the utopia of art par excellence, to which they commit themselves while dismantling it at the same time.

However, part of their subtle explanations is to be understood as verbal camouflage. They had to get used to this method after they dared to include some less than flattering pictures of the El Comandante in an already very critical exhibition in 1989.

René Francisco and Ponjuán still live in Cuba. This must be emphasised because hardly any of the figures from the internationally praised movement of young Cuban artists from the 1980s is still on the island. The greatest exodus of Cuban artists since the 1930s is now taking place, a mass emmegration of all those who find any chance to leave the country.

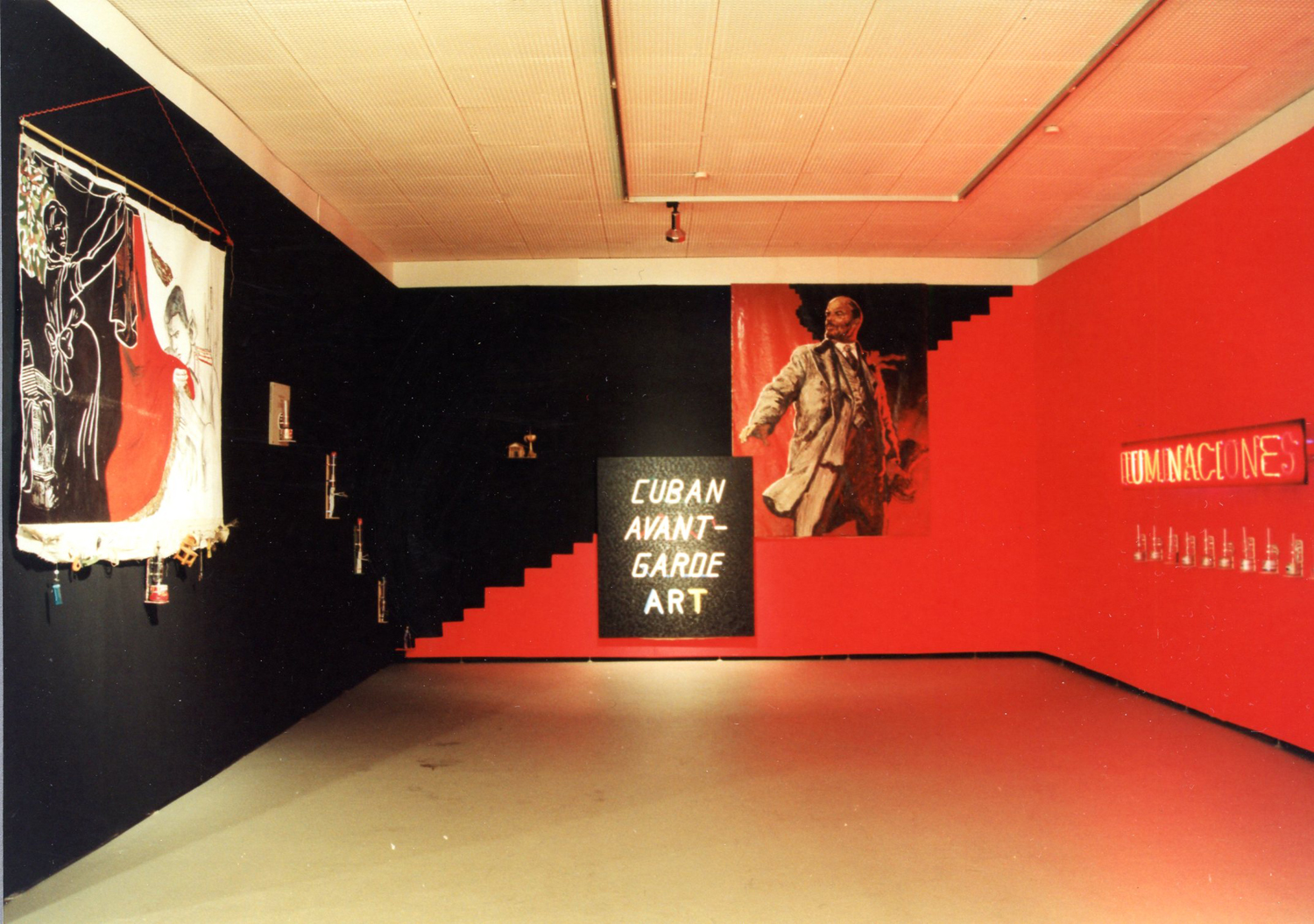

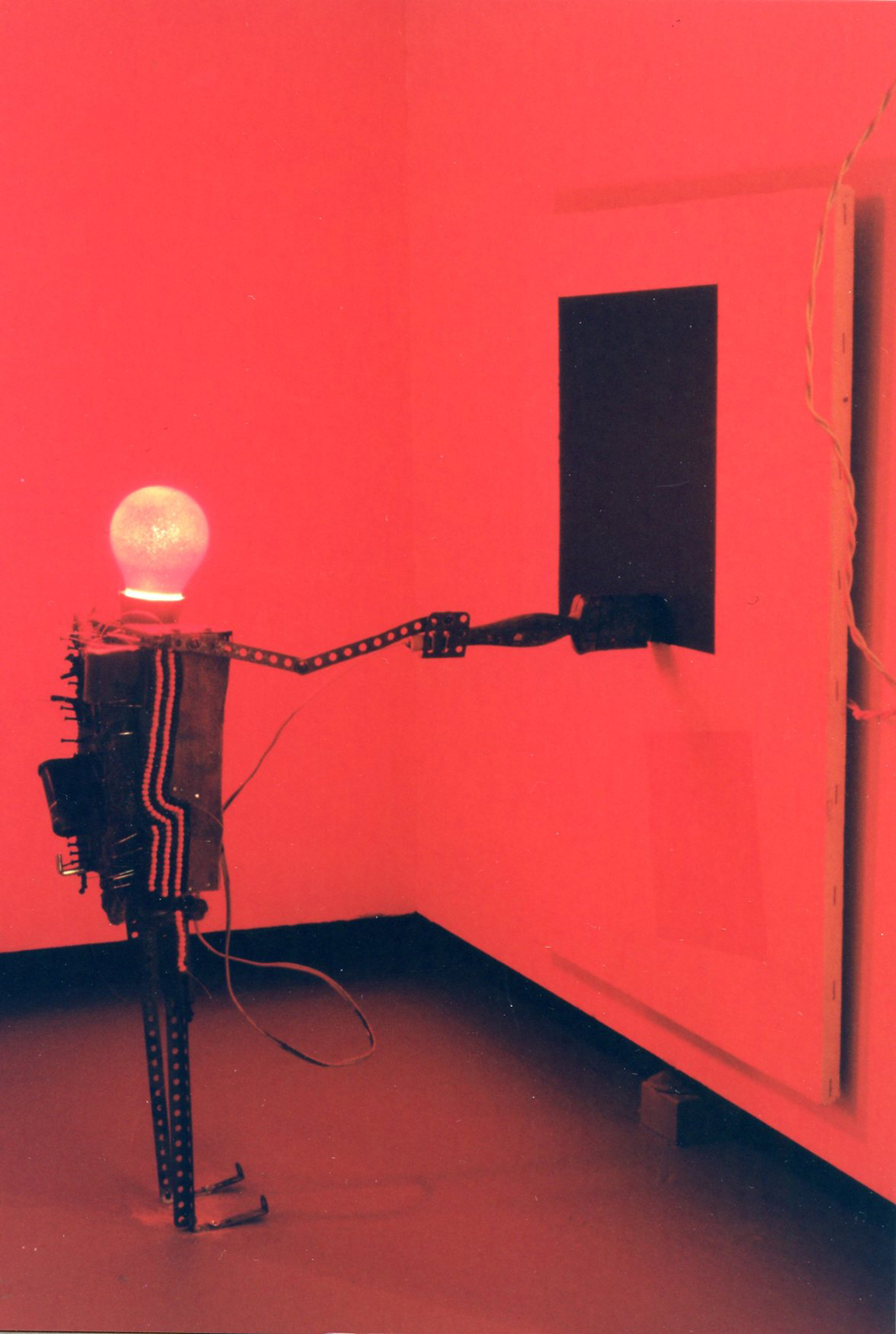

In the exhibition “Vuelo,” an installation conceived and realised especially for the ifa Gallery, the duo pulls out all the stops of its formal inventiveness, which a critic once described as postmodernist fireworks. In doing so, they unabashedly appropriate what seems useful to them from all epochs, currents, and cultural circles. Malevich is their symbolic figure of the utopias of the avant-garde. They present interpretations of the Russian’s peasant images from the perspective of their own cultural tradition and reflect the dissolution of the utopian conception of society in their country. The reinterpretation of heroic portraits of Lenin and workers in a socialist-realist style has a similar backstory. Lenin’s words about electrification as a prerequisite for communism are related to Cuban reality. Kerosene lamps made from Western beer and Coke cans, with which Cubans today have to make do during the frequent power cuts, are on view next to neon lettering that reads “Iluminaciones”.

Ponjuán and René Francisco often personify themselves and the figure of the artist as anthropomorphic tubes of paint. In “Vuelo”, they reflect on their position and on that of other artists in their country in relation to the art context of the “West” in a plethora of objects and assemblages. There is, for example, an imaginary dialogue taking place between Cuba and Joseph Beuys via a beer can telephone, like the ones children once built out of cream cans.

Other works are, just as ironically, dedicated to the Western collector of “Third World” art. The duo has been very occupied with this theme in recent times. At the V Havana Biennial in May/June of this year, they showed an installation entitled “Dream, Art and Market”. Among other things, it deals with the passion of the German collector Peter Ludwig for Cuban art, which was ignited a few years ago. The work will soon be on view in Aachen, Germany, when the Ludwig – Forum shows the Havana Biennial there starting on September 15. Ludwig has already purchased several paintings by René Francisco and Ponjuán in previous years. In 1992, the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf included one of them in the “Art & Campaign” exhibition, where it hung alongside works by such celebrities as Jeff Koons and Gerhard Richter.